Saki's From Zero to Hero Romhacking Guide Part 1: C & ASM Basics

Ahhh, "Romhacking", what a wonderful word. Whether someone modified a game's code in order to make it behave in ways its' original developers never intended, or perhaps someone who edited a game's sprites to insert their name in it, a custom soundtrack, or a complete retranslation of a game's fan into a new language, as soon as a game's files have been tampered with, and the game can still be booted, it all is romhacking.

As such, in order to avoid any further ambiguity, allow me to give a clearer meaning to this entry's title: there are many guides about "hacking" a game by simply ctrl-Fing through its' binary data and editing a string to your liking, or perhaps using a third-party tool to insert your sprites and songs in a streamlined manner; covering those aspects of romhacking sounds futile, any person capable of using a computer can understand how said tools function.

What I will cover will concern the programming side of romhacking, the most intimidating and least centralized one. Or well, it is technically centralized, but you don't really know where to begin, and I will try addressing that. As such, whenever I say something about "romhacking", you can interchange it with "programming" to avoid any confusion. First, we'll review the technical knowledge you need to already have in order to get anywhere, then we'll see how to "reverse engineer" and "debug" a game (quotations needed, we won't be very good at it, but enough to make what we want happen with enough patience and effort). Without further ado, let's get into it !

When you first look into romhacking, you might have heard that a good understanding of C and the Assembly of your "target" machine are required, or to the very least of a great help. This wouldn't be an incorrect advice, but it also doesn't tell that much, does it ?

What is an Assembly, or a target machine? I've heard of C before, but not the other thing...

Why C and ASM in particular? Why not Python, or Javascript, or Rust or whatever else ?

What is a good understanding of C? Could you understand C well if you're used to other programming languages ? Which ones ?

Let's try responding to all of those questions at once. So first of all, let's address the most important piece of knowledge about romhacking, aka what Assembly even is.

An Assembly language (there are many of them but they all follow similar base principles) is a low-level language that's supposed to make it easy for a human being to order a machine

to run instructions, or follow orders if you prefer.

We call it "low-level" because ASM is one of the closest layers of abstraction you can reach, between unreadable machine code (0111010101010100001), and a sentence a human could understand (x + y = z).

In low-level languages, you have to care for the particularities of the machine

you're currently working on: memory management, "registers", direct communication with the hardware you're using are given to you. The higher your language, the more you "abandon" those features to let the programming language you're working with

do the magic in your stead : you usually won't have to care about how many bytes your variables take up in memory, or if the code you've written runs on anything else than your own hardware. Let us not get into details too much for now.

For now let's just try understanding why we even care for that in the first place.

And indeed, why would it have to be C or ASM ? The easiest way to answer that question would be because that's how the original devs wrote the game's code most of the time. Sometimes it doesn't stand true, but the older your game the more accurate that will be.

In all cases, the second answer still applies to this day, and that's because this is what we can work with without the original source code.

There is a saying that has been quite popular for a while amongst reverse engineers and romhackers: "Everything is open source if you know assembly". That is because as long as you have a program's executable file, which is nothing more than the "machine code" mentioned above, there are tools out there which can reverse the compilation process, and re-interpret that code into assembly, provided that you know which exact machine/CPU Architecture your program targets (a program written for an x86-64 CPU won't have the same instructions as an ARM64 one for example): we call said process disassembly for machine to ASM code conversion. Some of these tools can go a step beyond, and transpose the somewhat human-readable assembly code into an even more readable C-like pseudocode ("pseudo" since the code wouldn't run as a program as-is, but we as humans understand the intentions behind it). If the produced code can actually be compiled and ran, either through manual work or by the program itself, we speak of decompilation.

C has all we need to easily transpose concepts that are important in ASM:

We actually care about a variable's type as that will dictate the size said variable takes in memory, and which values are valid for it or not: ASM usually have specific instructions depending on the size of the value you currently want to calculate (in x86 assembly for example, you have "movb", "movw" and "movl" instructions, depending on if you want to move 1, 2 or 4 bytes of a value into a location in memory, more on that here).

We also care for memory management: in C, thanks to the concept of pointers, you can tell where exactly in memory some specific data is used.

Overall, the language has been thought of as a middleman between ASM and a human's intentions (back when it tied to Unix's development), and there are ways of compiling C code directly into Assembly in a manner where it's "easy" to read what C code corresponds to what ASM instructions if you're well-trained (or if you experiment with the Compiler Explorer).

Before dissecting different aspects of the C language, let's bring out our good ol' friend Hello World! to have a somewhat clear idea of how code is even structured in C. It might not look that way, but a lot could be inferred even from the simplest examples!

#include <stdlib.h> int main(int argc, char** argv){ unsigned int x = 42; printf("Hello World! %d\n", x); return 0; }

From this code alone, we can tell that C doesn't care about indentation like it's the case in Python 3, and uses the good old braces as delimitations of a function instead. Speaking of, we do indeed have functions, whatever that means! It also looks like we have variables, we have one named "x" that takes the value 42 here. In C, all variables and functions must be typed, have an alphanumerical name which starts with either an underscore or a letter (they can also include numbers in other letters like "function999"). Functions in particular also take a certain number of parameters in parentheses (we write "()" if there aren't any), and have a return value (here the main function returns "0"). We can also see that a function can call another (our "main" function calls something called "printf" and sends it the sentence "Hello World!"). Finally, this is not anything explicit, but main is a special function name, our program's entry point, the first thing our executable will run. Finally, we can deduce that the language supports external libraries as we seem to "include" something into our code, and magically make the printf function (that we haven't declared anywhere) work. Overall, the language seems to be of the imperative type: we run instructions one by one, and said instructions will change something about our computer's memory or behaviour.

...

Alright, let's take it easy once more. A C program, at its' core, is a program, usually written into a .c file and compiled into an executable, that contains a main function, and a bunch of instructions (or not).

This is a valid C program:

void main() {}

This is also a valid C program:

int main() { unsigned x = 15; if (x > 57) { return 0; } else { return 1; } return 2; }

This is valid C code, but can't be a program on its' own, as we haven't defined any main functon:

int return_9(){ return 9; }

This is a "valid" C program, although the compiler will warn you that your main will be of type "int" by default:

main(){}

Even this is a completely fine and valid C program that will display the current Moon Phase to your favorite terminal:

#include <time.h> #include <stdio.h> a,b=44,x, y,z;main() {!a ?a=2551443,x= -b ,y=2-b,z=((time ( 0)-592531)%a<<9)/ a :putchar(++x>=a?x = -b,y+=4,10:x<0?x= x *x+y*y<b*b?a=1-x, - 1:x+1,32:"#."[( x <a*(~z&255)>> 8) ^z>>8]),y> b?0 :main();}

This isn't valid C code though, can't forget about the parentheses after your function's name:

void main { printf("Hello World!") }

So, a function, what's that? In C, we can interpret it as a chunk of code that will perform the instructions you've put inside. It's not exactly the same as a mathematical function, as you can under some conditions obtain different results from running a function with the same argument, but if you're familiar with a syntax like f(x) = x + 5 then you won't be too lost.

That x is called the parameter of a function: when we'll call our function from somewhere else in the code, in order to replace x by an actual value, we'll write something like f(20) or f(45974). Our function will then take that value and do something with it (or not), in our case add 5 to the value and return the result of the operation "x+5": we won't modify the original value of x, instead we'll tell the program "ok this is the result, do whatever you want with that".

NOTE: functions by default do "nothing" once defined. The CPU will only run them if they are called from the main function, or at least from a sub-function that was called by the main one.

Because we don't want to be limited to function parameters as the only way of declaring values in our code, we need to introduce another concept: the variables. A variable is the association of a name with a specific spot in memory our program has access to. There are two phases into making a variable: declaration and definition. When we declare a variable, we tell to which type it belongs: this is important as data types in C have a precise length, an integer won't have the same amount of memory allocated as a single character for example. If we wanted to declare a variable named "x" that would depict an integer, we would write the following:

int x;

Once that instruction is read by the CPU, it will allocate some space in memory to welcome our variable in. But of course, since we only declared the variable, it wouldn't hold any value (or, well it could but we'll see that later), not any that we decided to put there at least. This is where the definition comes in: defining a variable is telling our C program, that we'll give it a specific value. For example, if we assume our x variable to already be declared, we can write the following:

x = 57;

Now, our program knows that whenever we mention a certain "x" in an operation, its' value should be replaced by 57. By default, variables can be redefined, and the program would replace the variable's value in an instruction by its' current value in memory. As such, we can do the following:

int x; x = 45; x + 10; /* 55 */ x = 20; 100 - x; /* 80 */

We can also increment and decrement a variable by adding/substracting its' current value to another integer:

int x; x = 45; x = x + 5; /* x = 50, we could think of it as new_x = old_x + 5 */ x = x - 30; /* x = 20, or newer_x = new_x - 30 */

And, because we don't want to waste precious time and (digital) ink, you can declare and define a variable simultaneously, like we've seen with the "unsigned x = 15" in the first example of valid C code. If they have the same type, you can also declare and define multiple variables on the same line, like the following:

int x = 0, y = 1, z = 2;

Alright, we've been talking about variable types but what are they exactly? Well, in short, it's the meaning you give to your variable: a character would be of type char, a decimal number with int, a floating point number with float, and so on. As said before, each type has a defined size, let's see why it matters right now. First of all, here is the table of valid types in C and their respective size (on a 32-bit machine):

| Type | Usual length (in bits) | Values Range | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| signed char | 8 | -128;127 | 'Y' |

| unsigned char | 8 | 0;255 | 'z' |

| short int | 16 | -2^15;2^15 - 1 | -2365 |

| unsigned short int | 16 | 0;2^16 - 1 | 4968 |

| int | 32 | -2^31;2^31 - 1 | -785902 |

| unsigned int | 32 | 0;2^32 - 1 | 97U |

| long int | 64 | -2^63;2^63 - 1 | -148L |

| unsigned long int | 64 | 0;2^64 - 1 | 4UL |

| float | 32 | 10^37 | 1.5f |

| double | 64 | 10^37 | 87.2 |

| long double | 128 | 10^37 | 4.61L |

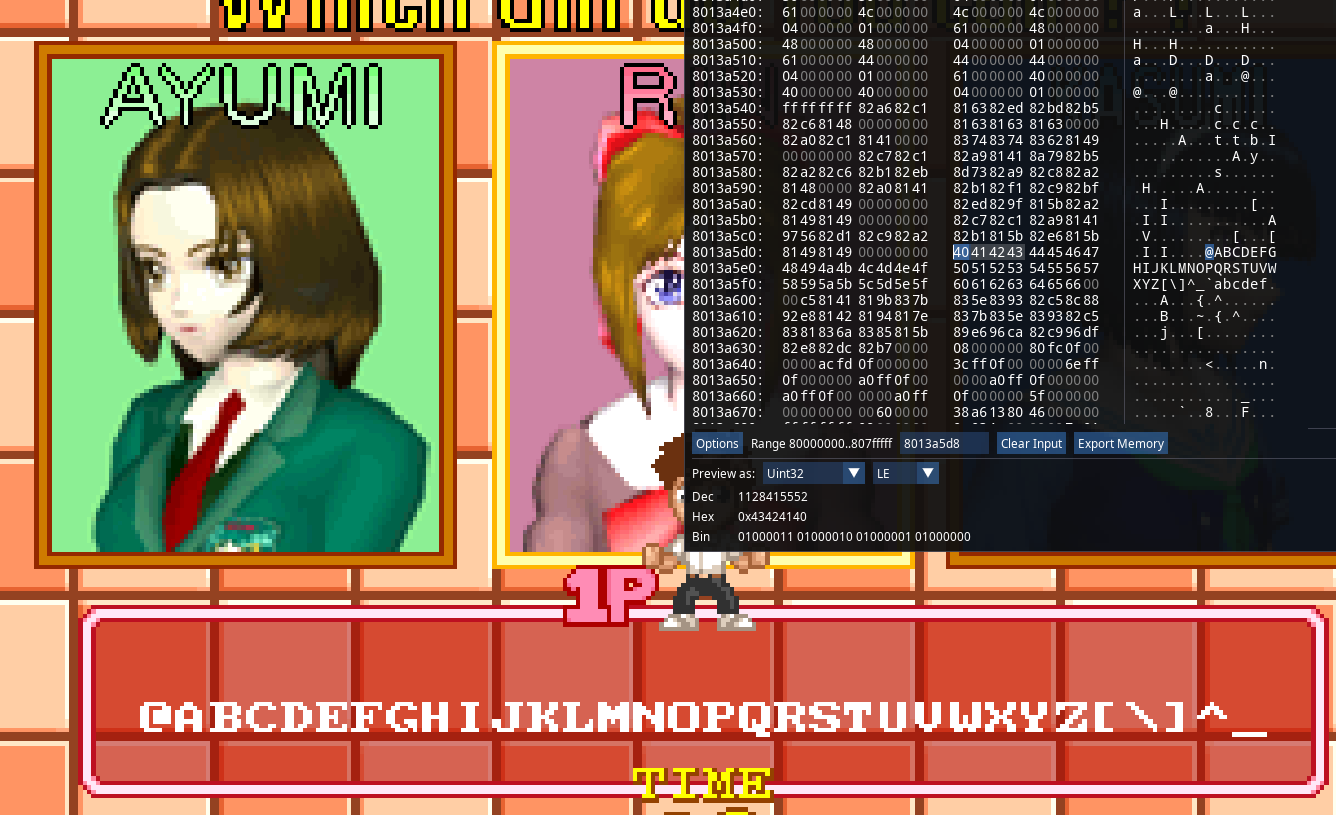

Because those sizes can vary depending on what machine you work with, you can always now a data type's size by using the function sizeof(type). Also, you might see an intriguing keyword in the table: unsigned. In order to understand it, we need to address the elephant in the room, and talk about how variables are stored in memory, or to say it more clearly, how values are represented for a machine to understand.

As we've said before, "machine code" is nothing but a bunch of 1s and 0s that our computer knows how to interpret. This doesn't only apply to the program's instructions, but to variables themselves as well. As such, to understand it you need to know about binary numbers, and number bases in general.

Usually, the base you're most familiar with is the decimal base: base 10. A digit can go from 0 to 9 to represent the units, then we add a second one for the dozens, a third one for the hundreds, etc...

What we do under the hood when we mention a number like "157", is the deduction that 100 + 50 + 7 are equal to that. In other words, we have:

157 = 100 * 1 + 10 * 5 + 1 * 7 = 10^2 * 1 + 10^1 * 5 + 10^0 * 7.

Indeed, in base 10, the first digit is equal to itself, and the digits to its' left are equal to themselves, multiplied by the next power of 10: 10^1, then 10^2, and so on...

Binary base, or base 2, operates in the same logic, except that the only valid digits in it are 0 and 1, and if we go above then we add another digit to the left. Let's take a small number as an example, 5.

First, we'll need to decompose it in powers of 2: 5 = 4 + 1 = 2^2 * 1 + 2^0 * 1 , or to be more explicit with the powers: 5 = 2^2 * 1 + 2^1 * 0 + 2^0 * 1.

Now, we only need to convert any existing power to a 1, and any in-between to 0: 5 = 101. And this "101" is the value that would be stored in your machine's memory.

To be more precise, because C cares about the concept of memory alignment, we would have padding bits depending on the type of the variable that stores this value:

a char takes up 8 bits, so it'd be 00000101, a short takes up 16 bits, so it'd be 0000000000000101, etc.

When a value is signed, the last bit is reserved to tell whether it's positive or negative, we call it the sign bit. When it is unsigned, the value can simply not be negative, as its' last bit would be treated like another power of 2. For example, the value 11111111 would be equal to -128 for a signed char, but 255 for an unsigned one. You can read more about the way negative numbers work in C here.

Binary is cool for computers, but it's a real chore for humans to deal with. As such, there are two other bases, which are both multiples of 2, that we can use: octal (base 8) and hexadecimal (base 16).

The octal base... exists. It won't be used very often, but it's a base in which digits go from 0 to 7. It's useful if you work with powers of 8, or binary numbers that has an amount of digits multiple of 3.

For example, the binary value 111 can easily be interpreted as 7 in octal base, so 111 111 would be 77.

The hexadecimal base on the other hand, is used all the time. As its' name indicates, it's the base 16, in which digits go from 0 to 9, then A-F for numbers which would be equal to 10-15 in decimal base. This base is very useful, as it allows us to group into a single digit a group of 4 bits.

And this is why we use Hex Editors to edit a program's data, rather than... Oct Editors ? Binary Editors ? Decimal Editors ??? In any case, we don't do that. Another cool thing about those bases, is that C natively understands them!

If you want to use a hexadecimal number, you prefix it with a 0x, like in 0xDEADBEEF, and if you want to use an octal number you prefix it with another 0, like in 077.

You can also use the 0b prefix for binary numbers, like in 0b10101011, but beware as this is not a standard feature of C so your compiler, such as GCC, needs to have that ability.

I won't enter in detail about how floating or double numbers work, it's honestly not something you'd need to care about much (although you can read more on it),

but I can at least explain why the shortest variable size, called "char", is able to store more than characters.

When I covered numbers, I've shown how we can quickly convert a decimal number into binary data readable by a machine, but what's the solution for letters and words?

It turns out that a standard (or a few rather, but we'll only speak of the one C uses by default) was established to associate a specific binary number to each letter, be it uppercase or lowercase, and then to digits, because we'd like to tell the difference between 1 as a number and 1 as a character,

and finally to other special characters. Overall, about 100 characters were given a value, which can be rounded up to 7 bits (0-127), or 8 bits with the sign bit always equal to 0 (-128-127 without the negative range): the American Standard Code for Information Interchange was born.

Enforcing a conditional limit on what value could or could not be a char would be unproductive, and so those 8 bits can be put to use, either to store an 8-bit number, or an ASCII character. In some cases, such as for Latin languages, those "leftover" values were used to encode even more characters and letters, in what's known now as "Extended ASCII".

To sum it up shortly, variables can be of different types and sizes, though most types are compatible with integers to some extent, which means that developers can favor one type over another for the sake of saving up space (if we're using a variable that won't go above 100 we can have a char for example). We will usually encounter them in hexadecimal format because CPUs tend to work with bytes, and bytes are easily represented as pairs of hexadecimal digits.

Another important thing to know about variables, is that they have a scope: variables declared outside of any function are called global and can be seen/used anywhere, whereas variables taken either as the parameter of a function or declared inside one are local, and would throw out an error were you to call them outside of where they were declared. Here is some valid code:

int a = 5; /*global*/ void increment_a(){ int b = 15; /*local*/ a = a +b; /*a = a + 15*/ } void main() { increment_a(); /*a = 20*/ increment_a(); /*a = 35*/ increment_a(); /*a = 50 */ a = a + 100; /*a = 150 */ }

And now some invalid code:

void local_a(){ int a = 15; /*local*/ } void main() { local_a(); a = a + 100; /*the main does not see a */ }

One last piece of trivia we can tell about variables before we'd need to introduce more concepts would be that in C you can declare constants. Indeed, if you add the keyword const before declaring a variable, you would render it unmodifiable beyond its' initial definition. This would also force you to declare and define simultaneously the variable, as C counts even the first definition as a "redefinition" if it's not done on the same statement as a declaration. For example, if I want to have a variable "a" that will always be equal to 5, I can write:

const int a = 5;

This is useful when you want to make sure the program isn't messing with a variable that isn't meant to be modified.

By the way, you can display a variable's value in your favorite terminal by using the printf function, it's very handy for when you want to debug stuff.

At many points, in the post above, we mentioned a variable's "location" in memory. We refer to such place most commonly as an address. If you use the printf command from above, writing printf("%p", variable) would show you the variable's address in hexadecimal.

Well, since we've talked of addresses, it's time to introduce one more variable type: the pointer. A pointer's purpose is to store an address, but because we want to treat the data located at that address as a variable, a pointer will also

need to know the actual type of the value we want to read. As such, even though a pointer type is mostly denoted with the * symbol, we actually need to write int* to make an int pointer, or char* for a char pointer, etc.

By itself, a pointer only stores an address. In order to read the value at said address, we need to dereference it by calling our pointer with a * prefixed to it.

Let's imagine that we have the value "0x12345678" at address 0x9ABCDEF0, we can access it with the following pointer:

int* addr = 0x9ABCDEF0; int value = *addr; /* 0x12345678 */

You can store an existing variable's address into a pointer by using the & operator. Invertedly, if you dereference a pointer, then assign a value to the resulting address (as in *addr = value), you overwrite what existed in memory there before.

This means that we can reverse our previous example, and store one of our variables into a pointer, for later use.

Let's imagine a funny example: suppose that I want to store multiple numbers one after another in memory. We will use the "start" variable's address as a start point. One funny gimmick of C is that incrementing a pointer by x will actually increment it by x*(variable size).

In other words, we can do the following:

int start = 0x01234567; /*let's say this is at 0x50000*/ int* addr = &start; /* addr = 0x50000*/ addr = addr + 1 /*addr = 0x50000 + 1 * sizeof(int) = 0x50004*/ *addr = 0x89ABCDEF; /*we store that value at 0x50004, so now the address range 0x50000-0x50007 is equal to 0x0123456789ABCDEF */

Sounds complicated ? Don't worry, with enough training, you can master the logic behind it.

int value = 10; /*variable at 0x12345 */ int* pointer = &value; /* pointer = 0x12345 */ int copy = *pointer; /* copy = 10 */ *pointer = 11; /* pointer stores "value"'s address so now value = 11 */

Here is a little game for you: try guessing what all of those variables are equal to after each and every instruction.

int main(void) { int a = 1, b = 2, c = 3; int *p, *q; p=&a; q=&c; *p=*q; p=q; q=&b; p=&a; *q=*p/(*q); return EXIT_SUCCESS; }

Also, before you ask: yes, you can make a pointer for a pointer. After all, the variable that stores an address would also need to have an address.

While we were working with pointers, we've seen an example where we store two integer values back to back so they'd be next to each other in memory. Manipulating pointers to that effect is annoying though, let's come up with something cooler: arrays! An array is a specific amount of values of a certain type that will be stored into a variable. Its' syntax is the following:

int array[4]; /*declaring an array of integers, its' size is 4... integers*/ array[0] = 5; /*defining a value for a specific index in the array*/ int value0 = array[0] /*accessing a value at a specific index in the array*/

More technically, an array could be seen like an alternative way of declaring and using pointers. we could rewrite the access to array[0] as *(array + 0),

like this StackOverflow post says, and like the C11 standard explains so well.

This access to a particular array index is referred to as array subscript. Decompilers will often generate pseudocode which randomly uses the pointer form at one place, and the array form at another, so it's important to know how to read both.

Generally speaking, the relation between an array and a pointer when it comes to manipulating values is pretty strong, and you can see a pointer as an array when it's suitable.

One of such cases would be the char* "array": C's way of representing strings.

In C, a string is an unknown amount of characters that ends with the null byte (or '\0'). If you write char* hello = "Hello World!", the hexadecimal data at the variable's address would have the ASCII representation of our string, followed by a 00.

Technically speaking, we created on the fly an array of 13 characters (the null byte also counts), or a char hello[13] = "Hello World!".

Since you have the ability to make pointers out of pointers, it also means that you can make arrays out of arrays: a multi-dimensional array is called a Matrix. The easiest example you can come up with is a grid. For a game of Tic Tac Toe for example, you'd need a 3x3 grid, which you can write as int grid[3][3];, with the first array corresponding to the x coordinate and the second one to the y coordinate.

Since we introduced the concept of pointers above, we can finally discuss an important subject when it comes to variable types: type conversion, also known as "casting". When you declare a variable of a certain type, it's actually possible to store its' value into a different variable of a different type. The syntax for that process, when it's done explicitly, looks something like short y = (short) x;. If you store an integer into a short, its' two smallest bytes will be preserved. Invertedly, if you store a short into an integer, 2 null bytes of padding will be appended to your current value.

unsigned int x = 0x12345678; unsigned short y = (unsigned short) x; printf("Hello World %02x", y); /*prints "Hello World 5678*/

unsigned int x = 0x12345678; unsigned short y = x; printf("Hello World %02x", y); /*also prints "Hello World 5678*/

Let's imagine that you have an int* and that you want to read its' values, not integer by integer, but byte by byte: how? The solution is to simply cast your int* into an unsigned char*. Now, you would be able to go through your addresses byte by byte, and interpret any value you encounter however you want.For Example, if we want to print our previous value of x, byte by byte, as it appears in memory, we'll do the following:

int x = 0x12345678; int* x_addr = &x; /*pointer to x*/ unsigned char* addr_to_char = (unsigned char*) x_addr; /*pointer to x that increments byte by byte*/ printf("byte 1: %02x\n", *addr_to_char); /*0x78*/ printf("byte 2: %02x\n", *(addr_to_char + 1)); /*0x56*/ printf("byte 3: %02x\n", *(addr_to_char + 2)); /*0x34*/ printf("byte 4: %02x\n", *(addr_to_char + 3)); /*0x12*/

This still doesn't explain what that void* deal is about. Usually, void is a special type that literally means "nothing". When a function returns void, it doesn't return anything. When a function's parameters list' is of type void, it expects no input arguments. The void* type on the other hand pretty much means the opposite: it's "anything". This type is mostly used for functions who want to receive data but don't care about their type (aka generic functions), such as Dynamic Memory Allocation functions (like free).

According to the N1256 C Standard (6.2.5 Types), "A pointer to void shall have the same representation and alignment requirements as a

pointer to a character type", so sizeof(void*) = sizeof(char*).

Note: standard C does not allow you to increment a void* by default, you'd usually need to cast it to char*.

Having data we can store, and manipulate, and display, is cool. You know what's cooler ? Being able to manipulate the flow of our program: sometimes we want to do one thing, another time we want to do something completely different! This is where Conditions come in. The most common syntax is the if (condition) {...} else {...}. Example below:

int x = 57; if (x < 0) { printf("negative number"); } else { printf("positive number"); }

In the example above, we skipped the line that'd print "negative number", because x's value was higher than 0. If the number was indeed negative, we would've instead skipped the "positive number" printf call. The second form of expressional conditions is the switch statement which does something depending on a variable's exact value. It follows the syntax switch(variable) {case value: ...; break; case another_value: ...; break; default: ...; break} . The default keyword is the "fallback" case when nothing else was met.

int x = 7; switch (x) { case 0: printf("0"); break; case 57: printf("is it actually 57?"); break; default: printf("nothing else matched"); break; } /*since x isn't equal to 0 nor 57, we'll print "nothing else matched*/

We can also use if-like conditions to make a program repeat a set of instructions until said conditions are met: loops. There are three types of loops: the for loop, the while loop, and the do... while loop. Since they all have their particularities, we will explain each of them in detail below.

Let's start with the simplest one: the while loop. This loop will repeat the set of instructions you wrote inside it as long as a specific condition is met.

int x = 7; while (x > 0) { x = x - 1; printf("%d ", x); } /*prints 6 5 4 3 2 1 0*/

The do... while loop is similar, but has one little quirk: it does what we write inside of the loop at least once, even if the condition is never met.

int x = 0; do { x = x - 1; printf("%d ", x); } while (x > 0); /*prints -1*/

The for loop is the most useful of them all, but also the hardest to explain. It takes the form for (int var = value; condition; var = another_value).

The first expression before an ";" is the initial execution, where we usually assign a variable to a value, the second expression is the condition we'll check for until it's met, and the final is applied after each return to the beginning of the loop, usually updating the previously assigned variable in the process.

int x = 0; for (x = 5; x < 21; x = x + 5){ printf("%d ", x); } /*prints 5 10 15 20*/

Each loop accepts the keywords break (force the program to get out of the loop) and continue (go back to the beginning of the loop no matter where we were).

In C, just as it's the case in many programming languages, you can use operators to act on variables and values.

We've already used some common arithmetic operators in our examples (+, -, *, /).

The ones we haven't seen are the Modulo (x % y) which returns the remainder of the operation x/y,

the Increment (++x/x++) (equivalent to x = x + 1), and the Decrement (--y/y--) (equivalent to y = y - 1).

Note: the position of the variable for your code will define whether the increment/decrement operation will return the old value or the new value.

int x, y , z; x = 100; y = --x; /* x = 99, y = 99 */ z = x++; /*z = 99, x = 100*/

You also have comparison operators (<, >, <=, >=, ==, != ) which are mostly used for conditional expressions, but actually return 1 if the comparison is correct, 0 otherwise.

int x = 50, y = 100, z = 0; x < z; /* 0 */ y > x; /* 1 */ x <= y; /* 1 */ z >= y; /* 0 */ x == x; /* 1 */ y != 100; /* 0 */

Then, we have some logical operators (&& (AND), || (OR), ! (NOT)) that could also be used in conditional expressions.

int x = 50, y = 100, z = 0; if (x < y && y > z) { printf("y is the biggest"); /*this will be printed*/ } else { printf("y isn't the biggest"); }

And finally, we have bitwise operators (& (AND), | (OR), ^ (XOR), ~ (NOT), << (Left Shift), >> (Right Shift)). Those operators manipulate a variable's bits' and are a bit tough to understand at first, but W3Schools has a decent explanation about them, and BitwiseCmd is an excellent playground for you to learn how any operator modifies your variables.

/*examples written with 32-bit architecture in mind*/ int x = 0xFFFF; x << 12; /*0x0FFFF000*/; x >> 16; /*0*/ x | 0xFFFF0000; /*0xFFFFFFFF*/ x & 1; /*1*/ ~x; /*0xFFFF0000*/ x ^ x; /*0*/

Note: although most developers can get away with not knowing how those work, it's in your interest, to not say mandatory, as a romhacker to understand how bitwise operations work, and how data is represented in its' binary form.

Remember when I said that we were definitely and absolutely done with variables and data types ? Well, turns out there's a last concept related to that: structs. A structure is a user-defined data type in which you declare a set of typed values that can then be stored in memory and accessed through a variable name. It is declared in the global scope, and follows the syntax typedef struct { type name; type2 name2; ... typeN nameN;}custom_type;. You can then declare a variable of type custom_type with the same exact syntax as usual. To define it, you'd access all of the struct's attributes one by one, and initialize them with a value. It's easier to use a struct than it is to define the concept, so let's create our own structure: I will create a structure that's meant to represent today's date in memory.

typedef struct { unsigned char day; unsigned char month; int year; } date; int main() { date today; today.day = 19; today.month = 10; today.year = 2025; printf("today is the %d/%d/%d", today.day, today.month, today.year); /* 19/10/2025 */ return 0; }

If the byte-sized types are too big or imprecise for your purposes, you can make use of Bit fields: as their name indicates, it will create variables which have the size equal to the amount of bits you want them to have. We can for example rewrite our date structure with bitfields.

typedef struct { unsigned char day : 5; unsigned char month: 5; int year; } date; /* now the compiler would yell at us if a day/month is bigger than 31 */ int main() { date today; today.day = 31; today.month = 10; today.year = 2025; printf("today is the %d/%d/%d", today.day, today.month, today.year); return 0; }

Honestly speaking, structures are a hassle to deal with due to all the implicit shenanigans related to memory alignment that happen in C, so working with them as a romhacker isn't the easiest, but it's still useful to know about. A structure's values are always put back to back in a memory area, so imagining the kind of structure a developer would write to save time and make their code more readable makes it easier to comprehend the data types a game might work with.

In C, whenever you want to use functions that were declared in another file, you use headers. With the keyword #include "file.h", we can import such headers and make our program aware of functions and macros which otherwise would not be defined. We used the stdio.h header from the "standard C" library a lot since we needed the printf() function to display a variable's value in the terminal. By the way, a library is nothing more than a collection of functions: it's where the stuff referenced by the headers we imported actually comes from.

A header is basically nothing more than a set of declarations of functions, variables/structures and constants, it can look like this:

#define SOME_CONSTANT 15 #ifndef __HEADER_H #define __HEADER_H int add_numbers(int x, int y); void do_something(); #endif

We would then have a "header.c" file which defines the functions mentioned in the header, and then our favorite compiler could take care of the rest.

Note: the header syntax of the form #ifndef CONSTANT #define CONSTANT ... #endif allows us to avoid compilation errors when the same header is imported multiple times and/or from multiple files.

As we said at the beginning of this chapter, the code your write in C eventually needs to be compiled into an executable binary. There are a few compilers out there, but the most widespread and supported ones you'd find would be The GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), which comes bundled with most Linux distributions and can also be installed on Windows machines with Minimalist GNU For Windows (MinGW), Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC), which is a Windows-focused C compiler. Sometimes you can find Clang being used in the wild, but the way that compiler (or compiler "front-end" actually, LLVM is the main technology at use) works is a bit different form the rest so let's forget about it for now.

Once you have a compiler installed on your computer, you should be able to run a command that looks like gcc file.c, and you'd obtain a .exe (or .out if you're on Linux) executable as the output. Sometimes, you'll need to feed multiple files in a row to the compiler (when you separate the main function and the secondary ones over multiple files for example). You can for example run a command such as gcc math_stuff.c graphics.c audio.c input.c main.c for a video game written in C, and you'd still obtain a single executable as the output.

The problem with compiling code this way, is that no matter if you changed a single file or your whole project, the compilation will start from 0 every time. You can solve this by using an intermediary step: object files. In GCC for example, typing gcc -c audio.c allows you to generate a file which ends with the .o extension, and that file could be re-used as-is during the general compilation process. In our previous example, we'd first generate .o files for every of our source .c ones, and then if we wanted to change the code of our input management, we could simply recompile as object the file input.c and build it with the rest by using gcc math_stuff.o graphics.o audio.o input.o main.o.

This process can quickly become redundant and hard to follow, so we came up with a way of automating a project's compilation and building process: Makefiles. If you have make installed on your computer, then running the command "make" or "make install" in a folder that features a file named Makefile would compile all you need in the way meant by the developer. Makefiles can have access to your OS' environment variables, which can be used to detect what compiler or libraries should be used. Learning how to use a Makefile optimally will be useful to solve dependency issues between some pieces of our code, and to speed up the building process generally. A "modern" build system known as CMake can help with generating makefiles.

Anyway, this knowledge isn't super important, but if you want to convert your C code into assembly, you can run gcc -S file.c and obtain the .s (assembly) file that you need. Most systems you'd target (ARM, x86_64, MIPS, PowerPC...) have some version of gcc that'd help you with compiling the code for the architecture that you need. Also, most compilers have a "flag" for Optimization, which would produce either smaller, or faster to run assembly without giving much consideration into how readable it'd be for a human, which is why it's so important to understand pointers, types, and operators, you can make sure that the compiler will replace an "i * 4" by "i << 2" if you read an optimized executable's pseudocode/assembly.

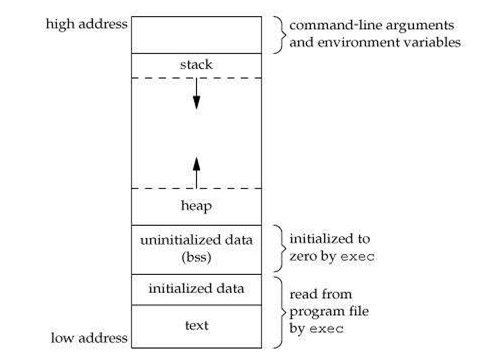

This section can really get big so I'll stick to the basics. A C executable is made of multiple segments: the "text" segment, which is simply our program's assembly code, the "data" segment where all of our global/constant/external variables are stored, the "bss" segment where all of the declared but uninitialized global variables are, then we have the stack and heap which are used for the actual memory management on runtime. We will focus on those two, as the rest barely matters.

The Stack is a concept that's mostly related to assembly: when we enter a function, we give it a "stackframe", and all the variables declared in the scope of said function, would belong to said stackframe. This allows to use a program's memory storage to bypass the (usually low) register count which couldn't store everything otherwise. All variables and data within the stack are managed by the program itself, and will usually be deleted/overwritten when we exit our function. The area/size allocated to a stack is constant.

The Heap differs from the stack in two ways: in contrary of the Stack, the Heap is a dynamically-sized area that expands whenever the programmer "allocates" (with malloc) a variable or a structure. Speaking of which, in contrary of the Stack, everything is allocated and de-allocated/freed manually within the Heap: once we exit a function, the variables we declared do not disappear and might be reused. It's unlikely a console before the PS1 era would make use of the Heap, but it's still good to know about it.

It's likely that whatever console/OS you work with has special functions, macros and memory areas for communicating with the hardware directly. Make sure you find a good documentation related to that, as developers, especially before the PS3 era, would tend to use those low-level communications for the sake of optimization. Homebrew console developers also tend to go low-level, especially when routines related to 3D graphics are to be optimized, Dreamcast devs show good examples of that.

Return to topWhen we saw C, we had a lot of "high-level" concepts to think about. In Assembly, we don't have any real types or structures, and memory management is left fully to the programmer's discretion. Therefore, even though the programs written in ASM are slightly harder to understand by a human at first glance, the actual language that dictates them is far simpler.

In ASM, the concept of variables isn't really a thing. Instead, we use Registers, which are a processor's internal storage. All registers will have a definite size, depending on which architecture is used, and if we want to store a value that's too small or too big, it will either be padded with zeroes (imagine storing an 8-bit number into a 32-bit register), or cut to fit into said register (if we store a 16-bit value into an 8-bit register, only said the first 8 bits will be read, if any). The CPU's amount of Registers will always be limited, very limited. It is also worth mentioning that not all registers are (directly) modifiable/accessible by the programmer in the first place, and that what you could or couldn't do depends on your architecture's specifications.

movl $0, %eax //eax = 0 movq $1, %rdi //rdi = 1

In ASM languages, you usually manipulate data either by writing to particular addresses in memory, or through the registers mentioned before, instead of clear variables. Everything you do is stored inside of a register, but unlike variables which you can create "infinitely", or rather within the limits of the resources you have, the amount of registers you have is finite and bound to your CPU's architecture. Theoretically speaking, this limits how much data you can work with simultaneously, although there is a way to bypass that with the Stack, in the same way as in C, except that this time it's up to us to manage the stackframes, which is usually done by using the push/pop instructions. In x86-64, the %rbp and %rsp registers are related to the Stack, so any local variable written in C will be stored there. Here is a very short and simple C code as example:

void main(){ int a = 15; }

And some ASM code that works in a similar logic:

movq $15, %rax // Move 15 into the %rax register, which we can then treat like the variable a

One funny quirk of assembly compared to C, is that we can force the program to reach any address we want for our next instruction: a specific register (usually called PC, Program Counter), is supposed to tell the program what instruction we were reading previously so we could know where to go next. The jumping instructions (usually of the syntax "jmp addr") will modify the PC register's value and keep the program going from an arbitrary address. We can use this gimmick to create infinite loops wherever we want! Here is an example where we infinitely increase by 5 the value of a register called "r0".

//imagine that the program starts at 0x1000 and the PC register increases by 1 with every new instruction add r0, r0, 0x5 jmp 0x1000

As manipulating addresses is not very convenient for a human programmer, we can give cute little names to a specific address in memory, that's all a label is. We could make use of that to jump to specific labels. Here is an example of ARM Assembly where we infinitely increment the R1 register by making the program jump to the line where the "loop" label is located:

loop: add r0, #1 // Add 1 to r0 b loop // return to loop label

The way conditions work in ASM usually, is that you'd have a "CMP op1, op2" operation that would modify some internal flags depending on the difference between both operands (that's how we call the "arguments" of an instruction, so a register, or a value), and then you could use conditional jumps (JE for equality, JNE for lackthereof, ...) to only jump to an address if a certain condition is met.

//same example as before add r0, r0, 0x5 //r0 += 5 and r1, r1, 0x0 //r1 = 20 cmp r1, r0 jne 0x1000 //loop until r1 = =r0

We can rewrite an if (condition) {a} else {b} statement by using conditional jumps in assembly. We can think of a C function that looks like this:

void main(){ int a, b; if (b < 7){ a = 5; } else { a = 13; } }

Which would give out the following ASM code:

.file "cond.c" .text .def __main; .scl 2; .type 32; .endef .globl main .def main; .scl 2; .type 32; .endef .seh_proc main main: pushq %rbp .seh_pushreg %rbp movq %rsp, %rbp .seh_setframe %rbp, 0 subq $48, %rsp .seh_stackalloc 48 .seh_endprologue call __main cmpl $6, -4(%rbp) //we compare b with 6 jg .L2 //jump if b is bigger than 6 (so b >= 7) movl $5, -8(%rbp) //we store 5 into a if we haven't made the jump (so if b < 7) jmp .L4 //we skip the L2 instruction to not store 13 into a .L2: movl $13, -8(%rbp) .L4: nop //end of function, your usual assembly shenanigans follow addq $48, %rsp popq %rbp ret .seh_endproc .ident "GCC: (x86_64-posix-seh, Built by strawberryperl.com project) 8.3.0"

When working with Memory in ASM, especially when manipulating the stack, you need to be aware of Memory Alignment, which would be given in detail in your architecture's Calling Convention . In x86-64, your stack's address must be a multiple of 16, or as the ABI (Application Binary Interface, a set of rules that define how compiled assembly code should work in the OS basically) would say, "The stack pointer holds the address of the byte with lowest address which is part of the stack. It is guaranteed to be 16-byte aligned at process entry."

Routines are the low-level equivalent of a function. Rather than having an explicit signature, they will simply be labeled by the programmer. The parameters are passed through specific registers (usually an ASM language's calling convention will tell the programmer which registers are expected to be used temporarily, and which are meant to last between multiple routine calls), and in the case we want to use registers whose values are meant to be preserved, we will store their values into a stackframe, then restore them at the end of our current routine: those are a function's prologue/epilogue. We can see the process at work with the following C program:

int add(int a, int b){ return (a + b); } void main(){ int a , b; a = 45; b = 57; add(a ,b); }

And the assembly code produced by a simple addition function when compiled with GCC:

.file "add.c" .text .globl add .def add; .scl 2; .type 32; .endef .seh_proc add add: pushq %rbp //assembly shenanigans related to stack alignment .seh_pushreg %rbp movq %rsp, %rbp .seh_setframe %rbp, 0 .seh_endprologue movl %ecx, 16(%rbp) //the actual function: we store %ecx and %edx into the stack movl %edx, 24(%rbp) movl 16(%rbp), %edx //now %edx takes %ecx's value, so it's equal to a, and eax takes edx's previous value so it's equal to b movl 24(%rbp), %eax addl %edx, %eax //a+b popq %rbp //more assembly shenanigans and end of function ret .seh_endproc .def __main; .scl 2; .type 32; .endef .globl main .def main; .scl 2; .type 32; .endef .seh_proc main main: pushq %rbp //initializing the stack and other assembly shenanigans .seh_pushreg %rbp movq %rsp, %rbp .seh_setframe %rbp, 0 subq $48, %rsp .seh_stackalloc 48 .seh_endprologue call __main //finally, we reach the main function and put our constants into the stack before loading them into registers, a is in %eax and b in %edx movl $45, -4(%rbp) movl $57, -8(%rbp) movl -8(%rbp), %edx movl -4(%rbp), %eax movl %eax, %ecx //we expect %edx, %ecx and %eax to be "free" to use for our functions according to the AT&T ABI, the add function will take those registers as parameters call add nop addq $48, %rsp //moving the stackframe and end of function popq %rbp ret .seh_endproc .ident "GCC: (x86_64-posix-seh, Built by strawberryperl.com project) 8.3.0"

This is the kind of forbidden knowledge that very few people, especially comp science teachers want you to know about, but you can actually write assembly code in C! The way to do it depends on which compiler you use, but both GCC and MSVC offers way to do it. You can then explicitly manipulate variables and write functions, like in the example below, where we write a's value into b:

int a=10, b; asm ("movl %1, %%eax; movl %%eax, %0;" :"=r"(b) /* output */ :"r"(a) /* input */ :"%eax" /* clobbered register */ );

You can also call and reference C functions in assembly. You will first need to declare an extern function somewhere in your ASM code, then you can call it and the compiler will understand what you refer to. Mathieu Gaillard shows a good example of that.

BITS 64; global main ; the standard gcc entry point extern printf ; declare a C function to be called section .text main: push rbp ; set up stack frame, must be alligned mov rdi, message ; first argument for printf xor rax, rax ; rax must be 0 (see explanations below) call printf ; call the printf function pop rbp ; restore stack mov rax, 0 ; normal, no error, return value ret ; return section .data message: db "Hello, World!", 10, 0 ; note the newline (10) and null (0) at the end

Now that you know the basics of Assembly, you should try writing some small programs in C, and train to convert them into assembly by hand. Turning an if/else into conditional jumps, making for/while loops with the same jumps, rewriting a function as a subroutine, your imagination is the limit but if you truly have no ideas, GitHub has some exercises here and there.

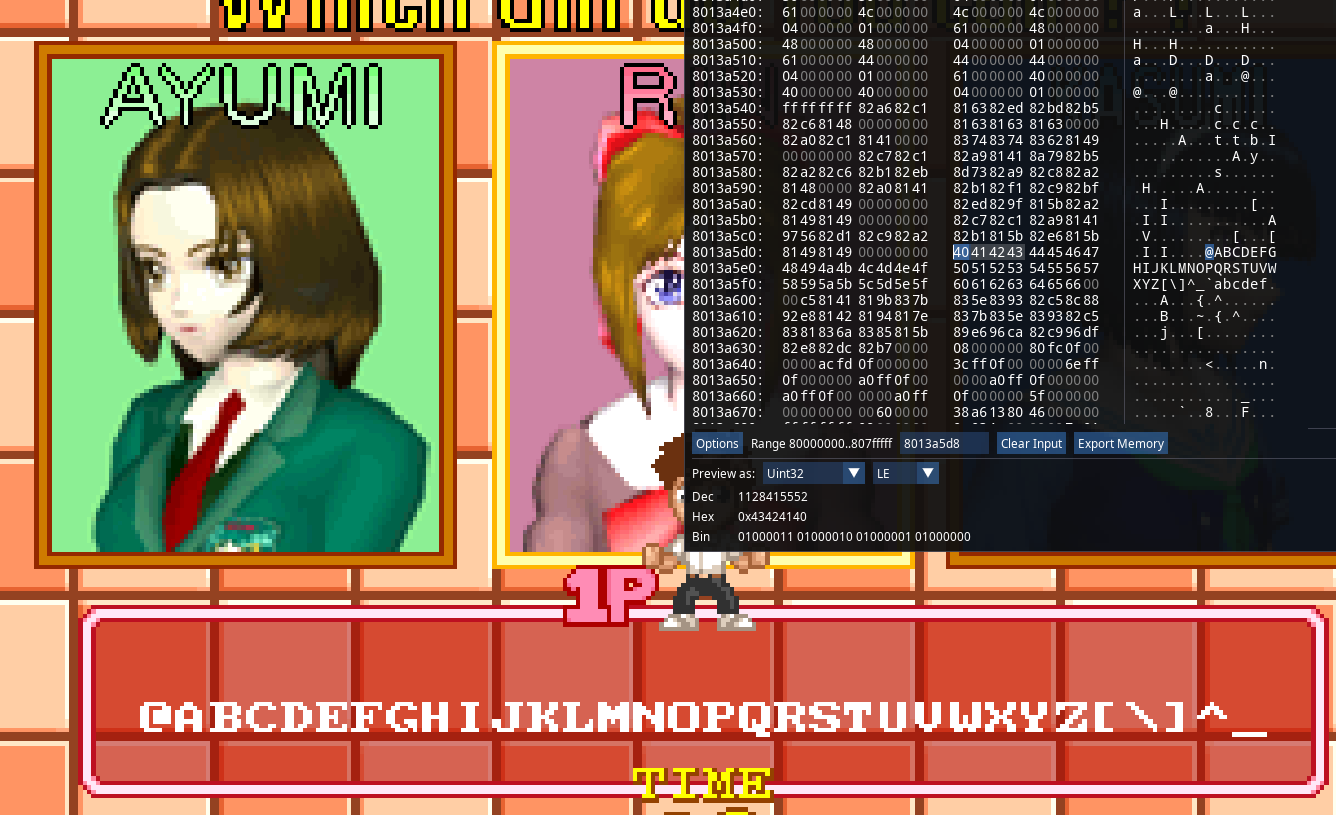

In my next post, we will start using Debugging and Reverse Engineering tools, and see in the process how C's logic carries over into ASM, and invertedly.

Previous Page